NOAA Teacher at Sea

Cathrine Prenot

Aboard Bell M. Shimada

July 17-July 30, 2016

Mission: 2016 California Current Ecosystem: Investigations of hake survey methods, life history, and associated ecosystem

Geographical area of cruise: Pacific Coast from Newport, OR to Seattle, WA

Date: Sunday, July 24, 2016

Weather Data from the Bridge

Lat: 47º32.20 N

Lon: 125º11.21 W

Speed: 10.4 knots

Windspeed: 19.01 deg/knots

Barometer: 1020.26 mBars

Air Temp: 16.3 degrees Celsius

Water Temp: 17.09 degrees Celsius

Science and Technology Log

We have been cruising along watching fish on our transects and trawling 2-4 times a day. Most of the trawls are predominantly hake, but I have gotten to see a few different species of rockfish too—Widow rockfish, Yellowtail rockfish, and Pacific Ocean Perch (everyone calls them P.O.P.)—and took their lengths, weights, sexes, stomachs, ovaries, and otoliths…

…but you probably don’t know what all that means.

The science team sorts all of the catch down to Genus species, and randomly select smaller sub-samples of each type of organism. We weigh the total mass of each species. Sometimes we save whole physical samples—for example, a researcher back on shore wants samples of fish under 30cm, or all squid, or herring, so we bag and freeze whole fish or the squid.

For the “sub samples” (1-350 fish, ish) we do some pretty intense data collection. We determine the sex of the fish by cutting them open and looking for ovaries or testes. We identify and preserve all prey we find in the stomachs of Yellowtail Rockfish, and preserve the ovaries of this species’ females and others as well. We measure fish individual lengths and masses, take photos of lamprey scars, and then collect their otoliths.

Otoliths are hard bones in the skull of fish right behind the brain. Fish use them for balance in the water; scientists can use them to determine a fish’s age by counting the number of rings. Otoliths can also be used to identify the species of fish.

Here is how you remove them: it’s a bit gross.

If you want to check out an amazing database of otoliths, or if you decide to collect a few and want to see what species or age of fish you caught, or if you are an anthropologist and want to see what fish people ate a long time ago? Check out the Alaska Fisheries Science Center—they will be a good starting spot. You can even run a play a little game to age fish bones!

Personal Log

I haven’t had a lot of spare time since we’ve been fishing, but I did manage to finagle my way into the galley (kitchen) to work with Chief Steward Larry and Second Cook Arlene. They graciously let me ask a lot of questions and help make donuts and fish tacos! No, not donut fish tacos. Gross.

Working in the galley got me thinking of “ship jargon,” and I spent this morning reading all sorts of etymology. I was interested to learn that the term crow’s nest came from the times of the Vikings when they used crows or raven to aid navigation for land. Or that in the days of the tall ships, a boat that lost a captain or officer at sea would fly blue flags and paint a blue band on the hull—hence why we say we are “feeling blue.” There are a lot more, and you can read some interesting ones here.

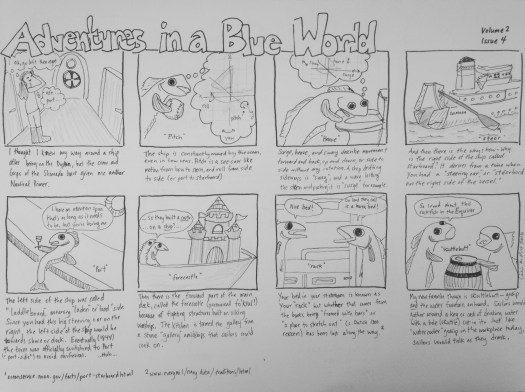

You can also click on Adventures in a Blue World below (cartoon citations 1 and 2).

And here is a nautical primer from Adventures in a Blue World Volume 1:

Did You Know?

Working in the wet lab can be, well, wet and gross. We process hundreds of fish for data, and then have hoses from the ceiling to spray off fish parts, and two huge hoses to blast off the conveyor belt and floors when we are done. But… …I kind of love it.

Resources

Etymology navy terms: http://www.navy.mil/navydata/traditions/html/navyterm.html

Interestingly enough, the very words “Sea Speak” have a meaning. When an Officer of the Deck radios other ships in the surrounding water, they typically use a predetermined way of speaking, to avoid confusion. For example, the number 324 would be said three-two-four.