NOAA Teacher at Sea

Jenny Gapp (she/her)

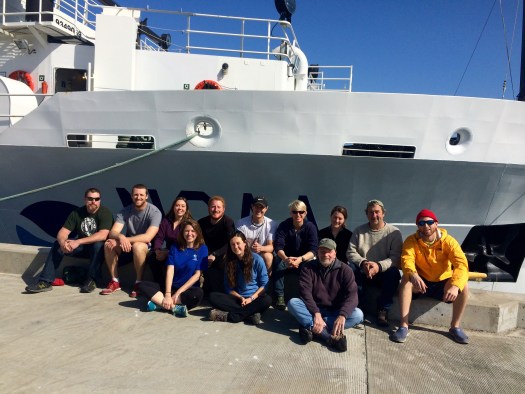

Aboard NOAA Ship Bell M. Shimada

July 23, 2023 – August 5, 2023

Mission: Pacific hake (Merluccius productus) Survey (Leg 3 of 5)

Geographic Area of Cruise: Pacific Ocean off the Northern California Coast working north back toward coastal waters off Oregon.

Date: Friday, August 4, 2023

Weather Data from the Bridge

Sunrise 0614 | Sunset 2037

Current Time: 0700 (7am Pacific Daylight Time)

Lat 43 16.7 N, Lon 124 38.0 W

Visibility: 10 nm (nautical miles)

Sky condition: partly cloudy

Wind Speed: 5 knots

Wind Direction: 030°

Barometer: 1020.3 mb

Sea Wave height: 1 ft | Swell: 340°, 1-2 ft

Sea temp: 13.7°C | Air Temp: 16.2°C

Science and Technology Log

On Wednesday night I stayed up to participate in the first CTD cast of the evening. What is a CTD? The short version: a water sample collection to measure conductivity, temperature, and depth. eDNA information is also collected during the CTD casts.

The longer version: As is true of all operations, all departments collaborate to get the science done. The bridge delayed casting due to erratic behavior from marine traffic in the area. When that vessel moved away, the deck crew got busy operating the crane that lowered the CTD unit to 500 meters. The Survey Technicians, along with the Electronics Technician, had just rebuilt the CTD unit days before, due to some hardware failures at sea. The eDNA scientist prepared the Chem Lab for receiving samples that would confirm the presence of hake as well as other species.

When I arrived, Senior Survey Technician Elysha Agne was watching a live feed of the sensors on the CTD unit. Agne explained what was happening on the feed: There are two sensors per item being tested, then both sensors are compared for reliability of the data. There is one exception: A dual channel fluorometer, which gauges turbidity and fluorescence (which measures chlorophyll). Turbidity spikes toward the bottom in shallow areas due to wave action. Salinity is calculated by temperature and conductivity. Sometimes there are salinity spikes at the surface, but it’s not usually “real data” if just one sensor spikes. The CTD unit is sent down to 500 meters as requested by scientists. Measurements and water collection occur at 500, 300, 150 and 50 meters. The number of CTDs allocated to a transect line varies according to how many nautical miles the line is. For example, multiple readings at the 500 meter mark may be taken on a line. CTD casts west of the one done at the 500m depth contour are spaced every 5 nm apart. Scientists are not currently taking CTD samples beyond the ocean bottom’s 1500m contour line.

The main “fish,” called an SBE 9plus, has calibrated internal pressure. As it descends you can tell the depth the “fish” is at. Sea-Bird Electronics (the origin of the SBE acronym) manufactures the majority of scientific sensors used on board, with the exception of meteorological sensors. The Seabird deck box (computer) is connected to the winch wire. The winch wire is terminated to a plug that is plugged into the main “fish.”

The other day, the termination failed. Termination means the winch wire is cut, threaded out, and the computer wire plugged into the winch wire. The spot it’s terminated can be exposed to damage if internal wires aren’t laid flat. Tension and tears may occur anyway because it’s a weak point. The plug on the main “fish” where the winch wire cable connects broke too, so the whole CTD had to be rebuilt. The “Chinese finger,” the metal spiral that pulls the load of the CTD on the winch wire, was also defective, so modifications were made.

When the CTD is at the target depth, Agne presses a button in the chem lab that logs a bunch of meteorological and location data. She remotely “fires” a bottle which sends a signal to the “cake” that sits on top of the CTD. The signal is an electric pulse to release a magnet that holds the niskin bottle open. If it pops correctly, water is sealed inside. Since two bottles of water were requested at each depth, a second signal is sent to the second bottle. There are 12 niskin bottles on the CTD “carousel.” After two were done at 500 m, the winch operator takes the CTD unit up to 300 m; Agne fires two more bottles there, then two more bottles at 200 m, 150 m, and 50 m. About two and a half liters of water are taken per bottle.

Once the CTD unit returned to the surface, I got to help “pop the nipples” on the bottles to release the water into plastic bags. Back in the Chem Lab, eDNA Scientist, Samantha Engster, pours the water through a filter 1 micron thin. The filter is then folded in half and placed in a vial of Longmire’s solution until the eDNA can be analyzed in a lab back on land. Microscopes are not used for DNA analysis. Phenol-chloroform is used to remove proteins from nucleic acids. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) technique is then used to perform gene expression. This is the third hake survey that has been done in conjunction with eDNA analysis.

While the CTD “fish” and all its sensors are collecting oceanographic data, Engster collects environmental data from the water samples. Surface water samples are also taken at the underway seawater station courtesy of a pump hooked up near one of the chem lab sinks. The eDNA verifies abundance and distribution of hake. When information from these water samples is partnered with data from the echo sounders, and “ground-truthed” with physical hake bodies in the net, the data set is strengthened by the diverse tests.

Career Feature

Note: A handful of the people I have met aboard are experienced “Observers.” NOAA contracts with companies that deploy observers trained as biological technicians. Find out more here.

Evan McNeil & Evan Thomas, Engineers

Give us a brief job description of what you do on NOAA Ship Bell M. Shimada.

Evan M.

I’m a manager over our engineers. Below me is the second engineer. We have three third engineers, a junior engineer, and an oiler, also called a GVA (General Vessel Assistant), or wiper. I set the pace of work everyday. I assign all the jobs. Traditionally the Engine Department is under the First Engineer, but technically the Engine Room is mine. The Chief Engineer and the Captain (NOAA Corps Commanding Officer in this case) are in charge of the safety of the whole ship. The Chief Engineer also directs jobs to me that need to get done and I’ll delegate those jobs out.

Evan T.

Third Assistant Engineer, soon to be Second. I mostly fix stuff that is broken.

What’s your educational background?

Evan M.

I have a Bachelor’s of Science in Marine Engineering Technology with a minor in marine science from California Maritime Academy. I grew up near Bodega Bay, so my background is oriented toward the ocean. I really enjoy it.

Evan T.

Graduated from Cal Maritime, 2019. I grew up in Southern California, Redlands, a desert that somehow grows oranges. I applied to all the engineering schools in California, and Cal Maritime was one of the few that replied back. I said “Yeah, I could see myself doing this.” And here I am!

What do you enjoy most about your work?

Evan M.

I enjoy who I work with. It makes work go by quickly. I enjoy our schedule and our time off. This is what I enjoy about my NOAA job and about sailing jobs in general. Shore leave is a type of leave. There’s also annual leave and sick leave. We call it going on rotation or off rotation. Off rotation is usually for a month, and on rotation is usually two months. Every ship is different but that’s how it is for the Shimada, a two-on, one-off schedule. If you talk to other sailors they’ll tell you ratios for time on and time off. For example, I did Leg 2 of the hake survey, I’m on Leg 3, and then I’m off.

Evan T. Learning new equipment, new ways to do things.

What advice do you have for a young person interested in ocean-related careers?

Evan M.

If you are interested in going straight to being an officer, I would go straight to a maritime academy. It’s a very niche thing to know about. No one knows what they want to do at 19. NOAA’s always hiring. If you are interested in being an engineer, you start out as a wiper, then you can work your way up in the engineering department pretty easily.

Evan T.

Imagine being stuck in an office and you can’t go home for a month. Find something that will distract you when you are out on the ocean for weeks at a time. Hang out with people, play games, read a book. You have to be ready to fight fires, flooding, that sort of thing.

If you could invent a tool to make your work more efficient—cost is no concern, and the tool wouldn’t eliminate your job—what would it be and why?

Evan M.

A slide that goes from the bridge to the engineering operations deck.

Evan T.

I would go for an elevator on the ship.

Do you have a favorite book?

Evan M.

Modern Marine Engineering volume 1

Evan T. My 5th grade teacher wrote their own book that I found entertaining. I also liked Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain.

Vince Welton

Give us a brief job description of what you do on NOAA Ship Bell M. Shimada.

I’m an electronic technician. I deal with everything that has to do with electronics, which includes: weather, navigation, radars, satellite communications, phone systems, computers, networking, and science equipment. All the ancillary stuff that doesn’t have to do with power or steering. Power and steering belongs to the engineers.

What’s your educational background?

When I was in high school my father had an electronics shop and I worked with him. He was career Air Force and an electronics technician as well. My senior year of high school I was also taking night classes at a college in Roseburg, Oregon in electronics. I joined the U.S. Air Force and was sent off to tech school and a year’s worth of education in electronics. Then there was a lot of learning on the job in electronic warfare. I worked on B52s. I was a jammer. In order to learn that you had to learn everybody else’s job. That’s what makes mine so unique. You had to learn radio, satellite, early warning radar, site-to-site radar, learning what other people did so I could fix what was wrong with their electronic tools. I went from preparing for war to saving the whales, so to speak. Saving the whales is better!

What do you enjoy most about your work?

I enjoy the difficulty of the problems. We’re problem solvers.

What are the challenges of your work?

Problems you can’t fix! That’s what disturbs a technician the most, not being able to solve a problem.

What advice do you have for a young person interested in ocean-related careers?

The sciences are important no matter what you do. Having curiosity is the biggest thing. My hope is that education systems are realizing the importance of teaching kids how to think. Young people need to grow the ability to ask questions, instead of just providing answers.

If you could invent a tool to make your work more efficient—cost is no concern, and the tool wouldn’t eliminate your job—what would it be and why?

I think AI has phenomenal potential, but it’s a double-edged sword because there’s a dark side to it as well.

Do you have a favorite book?

The Infinity Concerto, by Greg Bear

The Little Book of String Theory, by Steven S. Gubser

What’s the coolest thing you’ve seen at sea?

Actually seeing a whale come out of the water is probably the coolest thing. Watching that enormous tonnage jumping completely out of the ocean. If you look out the window long enough and you’ll see quite a few things.

Markee Meggs

Give us a brief job description of what you do on NOAA Ship Bell M. Shimada.

I’m an AB, or Able Bodied Seaman. The job looks different on different ships. On the Shimada I stand watch and look for things that don’t show up on radar. Most ships you drive—only NOAA Corps Officers drive on the Shimada—I can drive rescue boats, tie up the ship, and do maintenance on the outside. I’m a crane operator. On a container ship you make sure the refrigerated containers are fully plugged in. On a refueling ship (tanker) you hookup fuel hoses. Crowley is a major tanker company. On RoRo ships (roll on, roll off) you work with ramps for the vehicle decks, transporting cars from overseas.

AB is a big job on a cruise ship. I did one trip per year for three years, then got stuck on one during the pandemic in 2020. On the cruise ship you stand watch, do maintenance, paint, tie up the ship, drive the ship. There’s even “pool watch” where you do swimming pool maintenance. You also assist with driving small boats and help guests on and off during a port call.

I’m a member of SIU (Seafarers International Union) and work as an independent contractor for NOAA. I like the freedom of choosing where I go.

What’s your educational background?

I’m from Mobile, Alabama. I spent four years in the Navy (my grandad served on submarines during World War Two), one year in active Navy Reserves, then eight years as a contractor supporting the Navy with the Military Sealift Command. I spent a year as a crane operator in an oceaneering oil field, and have an Associate’s Degree in electrical engineering. On the oil field job we used an ROV to scope out the ocean floor first. After identifying a stable location I laid pipe with the crane, and took care not to tip over the boat in the process! My first NOAA ship was the Rainier, sailing in American Samoa.

What do you enjoy most about your work?

I most enjoy meeting different types of people. Once you’ve been to a place you have friends everywhere. I also love to travel—seeing different places. It’s a two-for-one deal because once you’ve finished with the work you are in an amazing vacation place.

What advice do you have for a young person interested in ocean-related careers?

If ships interest you, do the Navy first. They pay for training, and your job is convertible. Becoming a merchant mariner is easier with Navy experience than coming straight off the street. There is a shortcut to becoming a merchant mariner, but you’ll have to pay for classes. Finally, always ask questions! Yes, even ask questions of your superiors in the Navy.

What’s the coolest thing you’ve seen at sea?

The coolest things I’ve seen at sea have been the northern lights in Alaska, whales, volcanic activity, and rainbow-wearing waterfalls in Hawaii.

Do you have a favorite book?

Some of my favorite books are Gifted Hands, and Think Big, both by Ben Carson. Gifted Hands: The Ben Carson Story was turned into a film with Cuba Gooding Jr in 2009. Another book that made an impression was Mastery, by Robert Greene. Its overarching message is “whatever you do, do well.”

Julia Clemons

Give us a brief job description of what you do on NOAA Ship Bell M. Shimada.

I am the Team Lead of the FEAT (Fisheries Engineering and Acoustic Technologies) Team with the NWFSC (Northwest Fisheries Science Center). The primary mission of our team is to conduct a Pacific hake biomass survey in the California Current ecosystem and the FEAT team was born specifically to take on that mission from another science center. The results of this survey go into the stock assessment for managing the fishery. Fisheries and Oceans Canada are partners in this survey. Hake takes you down many paths because their diet and habitat are tied to other species. For example, krill are a major prey item in the diet of hake, so understanding krill biomass and distribution is important to the hake story as well. Rockfish also have an affinity for a similar habitat to hake in rockier areas near the shelf break, so we use acoustics and trawling to distinguish between the two.

What’s your educational background?

My undergraduate degree from University of Washington was in geological oceanography. I began with NOAA in 1993 and worked for the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory’s Vents program to study hydrothermal systems. This involved a diverse team of scientists: chemical and physical oceanographers, biologists, and geologists. I got my Master’s in Geology at Vanderbilt but shifted to NOAA Fisheries in 2000 working in the Habitat Conservation and Engineering (HCE) Program where we looked at habitat associations of rockfish. We looked at ROV and submersible video of the rocky banks off Oregon to identify fish and their geological surroundings. The HCE program shifted its focus to reducing bycatch by experimenting with net modifications and I moved to the FEAT team.

What do you enjoy most about your work?

I think one of the most important components of Team Lead is to be a supporter—supporting the facilitation of good science, supporting people. I also think about what I can do to support the overall mission of NOAA Fisheries. That’s my favorite thing, supporting others. I love when the focus is not on me!

What advice do you have for a young person interested in ocean-related careers?

Think about ways you can put yourself in the right place at the right time. Ask about volunteer opportunities. Ask questions, explore, think about what you want to do and look at people who are doing that—ask them how they got to that position.

What’s the coolest thing you’ve seen at sea?

When I was with the NOAA Vents group in 1994 I got to go to the bottom of the seafloor in the submersible Alvin. I was in there for nine hours with one other scientist and Alvin’s pilot. You think you’re going to know what it looks like, because you’ve seen video, and you think you’re going to understand how it feels, but then you get down there and everything is bigger, more beautiful, in all its variation and glory. We navigated to a mid-ocean ridge system that had an eruption the year previously. There was bright yellow sulfur discharge on black basalt rocks… after all those hours looking at ROV video, to see it in person through the porthole was incredible.

Do you have a favorite book?

The 5 AM Club, by Robin Sharma. I’m a morning person, and this book lays out how to structure those early hours and set you up for a successful day. When I was little I loved The Little Mermaid story by Hans Christian Anderson—the original, not the Disney version. I grew up in Vancouver, Washington and was always asking my parents, “Can we go to the beach?”

Taxonomy of Sights

Day 11. Three lampreys in the bycatch! Risso’s Dolphin (Grampus griseus).

Day 12. Blue Whales! I guess they read my blog post about the Gordon Lightfoot song. What may have been a blue shark came up near the surface, next to the ship. Strange creatures from the deep in the bycatch: gremlin looking grenadier fish.

Day 13. Pod of porpoises seen during marine mammal watch.

You Might Be Wondering…

How often are safety drills?

Weekly drills keep all aboard well-practiced on what to do in case of fire, man overboard, or abandon ship. Daily meetings of department heads also address safety. One activity of monthly safety meetings is to review stories of safety failures on other ships to learn from those mistakes. Each time a member of NOAA Corps is assigned a new tour at sea they must complete a Survival-at-Sea course. The Fishery Resource Analysis and Monitoring division (FRAM) also requires yearly Sea Safety Training for the scientists. “Ditch Kits,” found throughout the ship, contain: a rescue whistle, leatherman, food rations & water, and emergency blankets. Additionally, there are multiple navigation and communication tools in the ditch kit: a traditional compass, a handheld Garmin GPS, a boat-assigned PLB (personal locator beacon) registered with the Coast Guard, and a VHF radio with battery backup providing access to marine channel 16.

After a tour of the engine rooms, I learned that the diesel engines also have built in Emergency Diesel Generators (EDG). If you look up at the lights on the mess deck you’ll see some of the light fixtures have a red and white “E” next to them. This label indicates which would be powered by the generators, and which would not.

Floating Facts

The NOAA Corps is not a part of a union, however there are unions that advocate for other NOAA employees. Licensed engineers are a part of MEBA, The Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association. Non-licensed positions are represented by SIU, Seafarers International Union. Both of these unions are a part of AFL-CIO, the largest federation of unions in the U.S.

I had been curious whether there was a database that housed an inclusive list of NOAA Fisheries field research, and NOAA did not disappoint. You can find the Fishery-Independent Surveys System (FINNS) here, and browse as a guest. I’m now brainstorming how I might use the database with students—perhaps as a scavenger hunt—to have them practice their search skills. You can search by: fiscal year, fiscal quarter, science center, survey status, and platform type.

Which Cook Inlet species is the subject of Alaska Fisheries Science Center (AFSC) 2023 research, which is underway in a small boat?

Hint: Raffi

Another tool I’m looking forward to using in the classroom is NOAA’s Species Directory, which can serve as a scientifically sound encyclopedia for ocean animal reports conducted by students.

Librarian at Sea

“The sea is a desert of waves,

A wilderness of water.”― Langston Hughes, Selected Poems

This quote from Hughes’ poem, Long Trip, had me thinking about the surface of the ocean. I have seen the surface in many states over the past days: soft folds, jagged white-tipped peaks, teal, turquoise, indigo. Sometimes there are long snaking paths of water that have an entirely different surface than water adjacent. Whether it is due to currents colliding, chemical process, biological process, temperature difference—I cannot say. If I were to anthropomorphize the phenomena, I’d say these lines are wrinkles, as the ocean creases into different expressions. A hint of what lies within and beneath.

It also has me thinking about the interviews I’ve conducted with the people on NOAA Ship Bell M. Shimada. I started with a superficial name and title, a face on a board near the Acoustics Lab depicting all hands on Leg 3. When I sat down to talk with people representing Scientists, Engineers, Deck Crew, Electronics, Officers, Survey, and Steward, I began to unspool colorful stories from a broad spectrum of life experiences, many from divergent habitats, all who have converged here to do in essence what the concierge at my Newport hotel said to me as I walked out the door, “Keep our oceans safe!” A tall order in so few words. From shore we’re a small white blip on the horizon; up close there’s a frenzy of activity, a range of expertise, a conviction that our actions can improve living for humans, for hake, and for all the species in Earth’s collective ecosystem.

Hook, Line, and Thinker

We opened up a hake in the Wet Lab today to find it had a green liver. Why? Parasites? A bacterial infection? An allergy to krill? There’s always more beneath the surface, more stories to suss out. This is what makes science exciting, what makes living with 30+ strangers exciting. It’s what I enjoy about teaching.

How do the albatross know when we’re hauling back a net full of hake? They seem to appear out of nowhere. First a couple, then maybe 40 of them materialize around the net, squabbling over fish bits.

Have you ever discovered something unexpected and wondered about its origins?

How could the scientific method support you in finding out an answer… or to at least develop a theory?

A Bobbing Bibliography

Known as “charts” at sea and “maps” on land, NOAA Ship Bell M. Shimada has a small library of charts. Find out more at NOAA’s Office of Coast Survey. Paper charts are actually being phased out. “NOAA has already started to cancel individual charts and will shut down all production and maintenance of traditional paper nautical charts and the associated raster chart products and services by January 2025.”