NOAA Teacher at Sea

Sue Oltman

Aboard R/V Melville

May 22 – June 6, 2012

Location: Puerto Ayora, Galapagos Islands

Date: June 6, 2012

Weather Data from the Enchanted Isles (Santa Cruz Island, Ecuador)

Air temperature: 82 F (feels hotter!)

Relative humidity: 73%

Precipitation: 0.0 mm

Personal log

The NOAA research cruise is over and we are now on land, but the elements of science are simply different.

The Galapagos Islands are part of Ecuador, on the equator and at about 90 degrees longitude west. The time is the same as Mountain Time zone in the United States. There are 12 hours between sunrise and sunset here – while my hometown is approaching the longest period of daylight of the year.

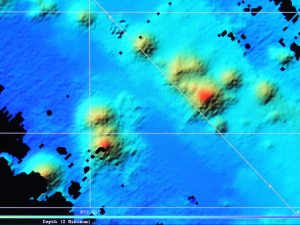

As we sailed into the islands, we could not be all the way into the harbor as the coastline is not only too shallow for the Melville, but rocky and ecologically fragile. Ecuador carefully inspects all boats – inside and out – that enter its waters. There are so many endemic species (found only here) and some are endangered, that they are vigilant to protect against the introduction of any foreign organisms, no matter how small. The Galapagos Islands are in a fracture zone and were formed by a hot spot – an opening in the slowly moving crust which allows molten rock to rise from the mantle. The hot spot – which changed directions at some point – has formed over 100 islands (some of them very tiny!) which comprise what is called the Galapagos Islands.

While the abundant animal life is really diverse and captivating (I’ll get to that next), the geology is beautiful as well. There is dark volcanic rock everywhere you look! It is even used in the walls of the buildings and sidewalks. It is mostly extrusive and mafic igneous rock, and one little island is a national preserve called Las Tintoreras, made completely out of Aa!

Even though there is black rock everywhere, there are still beaches with the finest white sand. Some places in the islands have red or green sand, depending on the minerals. Visiting a green sand beach is something I’d like to do, as I love rocks that have olivine. By the way, no rocks or any other natural material can be taken out of the islands. What I was able to take away were wonderful pictures and happily, some beach glass (litter, really) to add to my collection.

However, it is actually a lichen, which was able to establish itself on the nutrient-poor rock. With the process of succession, some small, low plants began to grow as have mangrove trees. Some areas look like there are lots of white pebbles, but it is actually small bits of coral or sea urchin spines – calcium carbonate. The two animals common in this particular area off of Isabella Island are white-tipped sharks (tiburones or tintoreras) and marine iguanas. There are some lava tunnels and channels which are great places for these sharks to hang out.

Marine iguanas are very different from terrestrial iguanas. As their name implies, they swim and they are also herbivores, eating only plants, algae in particular. They were everywhere in all sizes, but sometimes quite hard to see until you were right on top of them, as they blended in with the black rock.

It was mating and nesting season and the males sometimes change colors, to a reddish hue, at this time.

If a marine iguana looks like it is wearing a white hat, this is due to their bodies excreting salt – they do live in salt water, after all! Other animals seen in this area are two species of sea lions, one a small variety that makes you think they are all babies! Also, there is an endemic species of Galapagos penguins, much smaller than the Antarctic penguins we commonly think of.

Other birds included pelicans, frigate birds, and the Blue Footed Booby. From the boat, you could see the animals, birds and crabs on the rocks and the larger animals (sea lions, sea turtles, sharks, manta rays) swim near the boat. Since I was snorkeling, I was able to see all these cool creatures underwater swimming with me! Not only that, but there were a wide variety of colorful tropical fish and some eels. Animals that didn’t move were sea cucumbers, sea urchins and some that I will have to research to identify. Not too long ago, the sea cucumber was almost over-harvested to extinction here! It had become an edible delicacy for a while. However, one look at the reefs here will prove to you that this primitive and sometimes disgusting organism is back in force.

Scuba divers have a great opportunity to see hammerhead sharks which are in abundance in certain areas. Although I was not able to dive this time, therefore did not see them this time, but one of the scientists in the group, Sean, captured some amazing footage from his dives at Gordon Rocks and North Seymour.

On land, there are also a number of endemic species, the most famous being the species of giant tortoises that can live much longer than humans. The Charles Darwin Research Center is here on Santa Cruz and many tortoises are in natural habitats (albeit in fenced in areas). Surprisingly, they can be VERY active, sometimes a bit ornery towards each other, and even make noises!

The tortoises are herbivores and are fed a few times a week. The oldest and most well-known is a Pinta tortoise named Lonesome George. He is about 200 years old and is the very last of his species, so when he dies, the Pinta tortoise will be extinct. The research center tried several times to mate him to save the species, but it was never successful.

If you take a tour to the Highlands of Santa Cruz, up in the forests you can see many even larger giant tortoises than the ones at the Darwin Center, roaming freely about. Sometime in the future, I hope to do this. A neighboring and very “young” island, Isla Isabella, a 2 ½ hour boat ride away, has a terrific turtle research center, too. In my opinion, this was an even better place to learn about the developmental stages of the turtle from egg to the twilight years.

Birds are numerous and I mentioned several earlier, but Darwin was known for researching finches of which we saw many. My favorite was a little yellow finch and boy oh boy, are they hard to photograph! It was possible to get very close to the birds, perhaps even a couple of feet away.

Another recurrent daily scene was the fish market at a bay in Santa Cruz. Fresh catches were brought in, sold, and the fish often cleaned right there at special tables for this purpose. The pelicans were certainly omnipresent pests, but there also was always a sea lion there, begging for fish, and sticking his nose towards the table, just like a family dog would do!

There are many volcanoes here, some of which are still considered active, as is the case on Isabella. Scientists study the volcanoes here as well as the animal life. All around you, there is talk about respect for and conservation of the animal life, as well as preservation of the geological formations.

Although we did not have a lot of time here, it seemed like an appropriate place to terminate a scientific research cruise, with all of the geologic and biologic connections here. Many times throughout my stay, I couldn’t help thinking that this place would be the ultimate school field trip! Perhaps that will be a scientific adventure in the future.