NOAA Teacher at Sea

Theresa Paulsen

Aboard NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer

March 16-April 3rd

Mission: Caribbean Exploration (mapping)

Geographical Area of Cruise: Puerto Rico Trench

Date: April 2, 2015

Weather Data from the Bridge: Partly Cloudy, 26 C, Wind speed 12 knots, Wave height 1-2ft, Swells 2-4ft.

Science and Technology Log:

What are the mappers up to?

After we completed our two priority areas of the cruise, the mappers have been using Knudson subbottom sonar to profile the bottom of the trench. Meme Lobecker, the expedition coordinator sends that data directly to the United States Geological Survey (USGS) for processing. They returned some interesting findings.

The subbottom sonar sends a loud “chirp” to the bottom. It penetrates the ocean floor. Different sediment layers reflect the sound differently so the variation and thickness of the layers can be observed. The chirp penetration depth varies with the sediments. Soft sediments can be penetrated more easily. In the picture below, provided by USGS, you can see hard intrusions with layers of sediments filling in spaces between.

How does the bathymetry look?

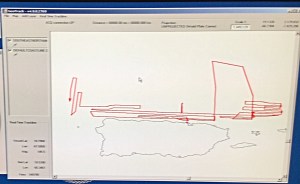

In the last two days, I have been really enjoying the incredible details in the bathymetry data the multibeam sonar has gathered. We mapped over 15,000 square miles on our voyage! Using computer software we can now look at the ocean floor beneath us. I tried my hand at using Fledermaus software to make fly-over movies of the area we surveyed (or should I say swim-over movies). Check them out:

I also examined some of the backscatter data. In backscatter images soft surfaces are darker, meaning the signal return is weaker, and the hard surfaces are whiter due to stronger returns. One of the interns, Chelsea Wegner, studied the bathymetry and backscatter data for possible habitats for corals. She looked for steep slopes in the bathymetry and hard surfaces with the backscatter, since corals prefer those conditions.

Chelsea Wegner Poster (pdf)

On the next leg, the robotic vehicle on the ship will be used to examine some of the areas we were with high-definition cameras. You can watch the live stream here. You can also see some of the images and footage from past explorations here.

This is a short video from the 2012 expedition to the Gulf of Mexico to tempt you into tuning in for more.

Personal Log:

The people on this vessel have been blessed with adventurous spirits and exciting careers. Throughout the cruise, I heard about and then came to fully understand the difficulty of being away from family when they need us.

I would like to dedicate this last blog to my father, Tom Wichman. He passed away this morning at 80 years of age after battling more than his share of medical issues. As I rode the ship in today I felt him beside me. Together we watched the pelicans and the boobies fly by. I am very glad I was able to take him on a “virtual” adventure to the Caribbean. He loved the pictures and the blog. I thank the NOAA Teacher at Sea program for helping me make him proud one last time.

“To know how to wonder is the first step of the mind toward discovery” – L. Pasteur. These words decorate my classroom wall but are epitomized by the work that the NOAA Okeanos Explorer and the Office of Exploration and Research (OER) do each day.

Thank you to the Meme, the CO, XO, the science team, and the entire crew aboard the Okeanos for teaching me as much as you did and for helping me get home when I needed to be with family. I wish you all the best as you continue to explore our vast oceans! My students and I will be watching and learning from you!

I would also like to thank all of the people who followed this blog. Your support and interest proves that you too are curious by nature. Life is much more interesting if you hold on to that sense of wonder, isn’t it?

Answers to My Previous Questions of the Day Polls:

1. Bathymetry is the study of ocean depths and submarine topography.

2. The deepest zone in the ocean is called the hadal zone, after Hades the Greek God of the underworld.

3. It takes the vessel 19 hours and 10 minutes to make enough water for 46 people each using 50 gallons per day if each of the two distillers makes 1 gallon per minute.

4. NOAA line offices include:

- National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service

- National Marine Fisheries Service

- National Ocean Service

- National Weather Service

- Office of Marine & Aviation Operations

- Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research

5. The pressure on the a diver at 332.35m is 485 pounds per square inch!

6. The deepest part of the Puerto Rico Trench is known as the Milwaukee Deep.

Thank you for participating! I hope you learned something new!